The Material Review

Issue 134: The Mike Sager Interview

Mike Sager is an author, reporter, and publisher whose career spans more than four decades. He’s written for The Washington Post, Rolling Stone, GQ, and Esquire, including stories that have gone on to inspire films like Boogie Nights and the TMR favorite, Last Tango in Tahiti. We caught up with him during his daily constitutional walk to talk about his long-lost story on yuppies (republished here for the first time), how he’s used appearance as a reporting tool, and doing shit his own way. Enjoy.

TMR: Let’s start with the “Demographic Man” (Read the Story Here). That seemed really interesting, and that’s the kind of thing we’re interested in at TMR — consumerism and the role brands play in people’s lives.

MS: I’ve done two versions of the story, years apart. The first ran in the April 1986 issue of Regardie’s, though it was never collected. Regardie’s motto was “Money, Power, Greed.” It was peak Gordon Gekko, Wall Street 80s. We all had silver baseball jackets with the slogan on the back. I used to love wearing mine while weaving my Honda CX500 Custom through D.C. traffic.

Shout out to Bill Regardie of D.C. and Key West, quite a character in his day. I still talk to him a couple of times a year.

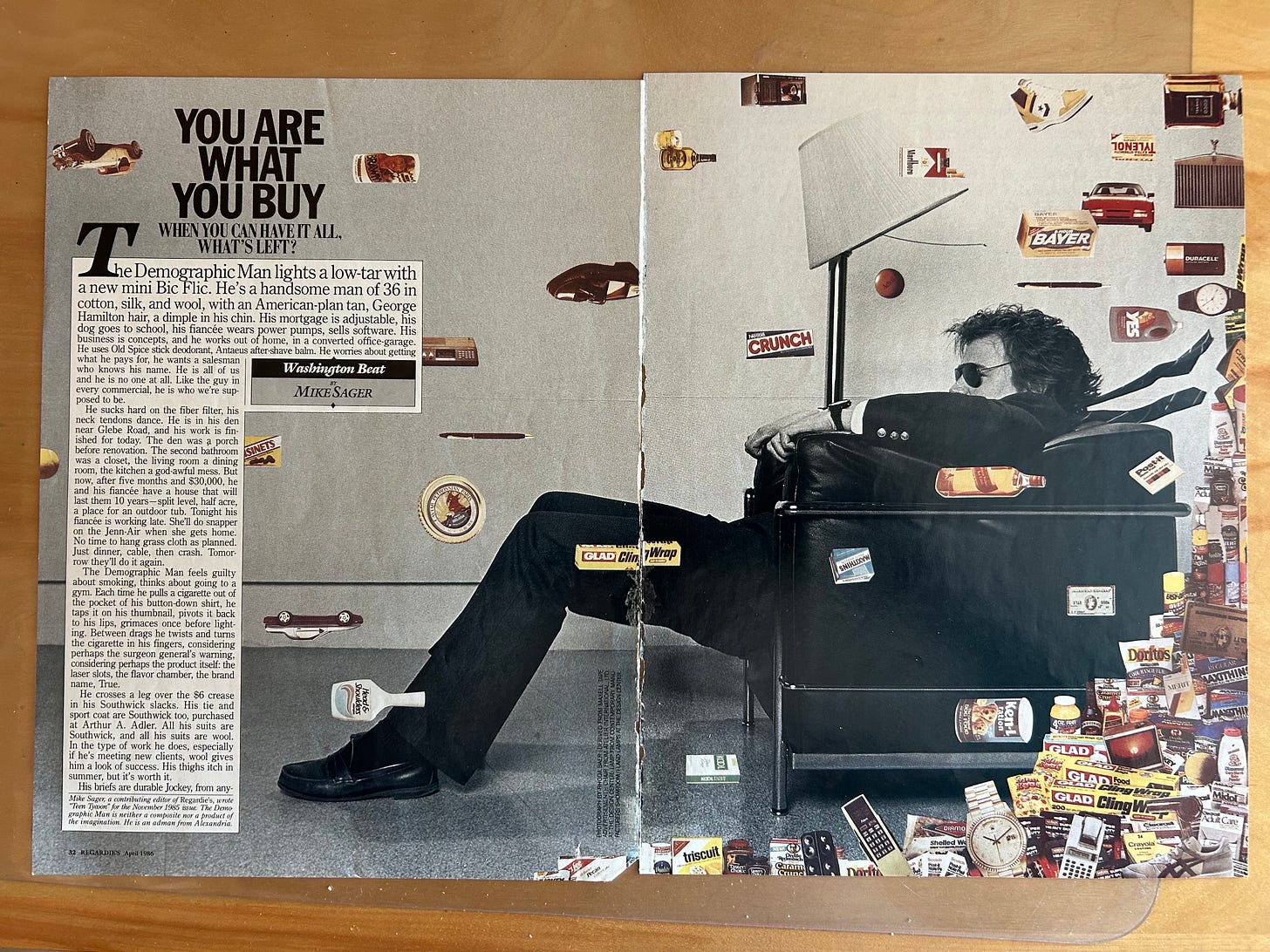

The Regardie’s artwork was a play on a popular Maxell campaign from the cassette boom. Their “Blown-Away Guy” ad, where a man sits in a chair blasted by sound, was everywhere. You could say it was the meme of its time.

The second version appeared in Esquire in 2009 and was later collected in my book The Someone You’re Not. It revisited the idea of “The Demographic Man.” Back then, Esquire ran “Esquire Man” contests for readers. The guy from that story was the 2009 winner. We still keep in touch.

TMR: Is there anything that sticks out to you, anything you took away from that experience?

MS: I felt that had I been Tom Wolfe, they’d have called them yuppies, the “Demographic Man.” There were always brands, and there was always brand loyalty. Sears, Fruit of the Loom, whatever. You bought the same ones and associated them with quality. But during the early 80s, the consumerist revolution really took off. Everybody had a brand identity and reasons for using everything. You could see the start of it.

I found it interesting that the concept has now been carried out to the nth degree. When I started freelancing, one of the first things people told me was, “Never change your byline.” I realized I was building my brand, even though nobody called it that back then. Now it’s branding.

I think the roots come from that early 80s consumerism, when baby boomers graduated from protesting into buying things. Slowly, consumerism became the religion of the entire nation and world. The actors and influencers are our gods and goddesses. We scuttle around on earth, seeing what they wear and do, and we want it too. That’s where we get our ethos.

Middle-class people and above wish for things and spend weekends buying them. I see it all in miniature: someone buys a jet ski, then has to buy two, then a double trailer, then a bigger SUV, then a bigger house because the garage is too small. That’s how the culture works, building upon building. Collecting. You start loving these things, want more, become an expert. My friends are like that with Scotch and bourbon.

So that’s where Demographic Man started. Going back to the artwork, when you think about the sound system itself, you couldn’t just have music. You had to have a whole component system: two big speakers, an equalizer, an amp, a turntable, a cassette or reel-to-reel. That kind of obsession with things, with the setup, separates humans from everyone else.

I was thinking of Jane Goodall the other day, how she said chimpanzees used tools. We’ve come a long way.

TMR: You’ve had so many different experiences through your work; is there anything you’ve collected or kept from assignments that you still have?

MS: I’ve always been big on pictures. I used to be a photographer, but I stopped carrying a camera, which I regret. People ask if I have pictures with people like Rick James, and I don’t, no camera phones back then. But I like pictures, well-made ones of people I’ve known. I collect those.

I’ve worked by myself for 34 years, so I need company. During COVID, I started making art out of the artwork used in my stories and books. I was printing, framing, filling bare walls with all this time and material I had. My walls now look like a gallery. People come in and say so.

Of course, I live in La Jolla, where people ask why I’m wasting so much square footage on a library. So you kind of don’t listen to the comments either way.

TMR: They think it should be a Peloton studio or something.

MS: I know it could be, damn it!

TMR: Is there anything someone’s given you from a story that you still have?

MS: There was a time when I’d take small things. I remember taking a photo from Hunter Thompson’s place. I spent three weeks with him, he’d been arrested, and I succeeded him as the drugs correspondent at Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner sent me to Woody Creek to write the story and basically babysit Hunter. He put me to work as his assistant because everyone else had run away. I’d spend the whole day with him, starting with the crushing up of a baggie of cocaine and moving on to the rest of the activities for the next thirty-some hours. I took an 8x10 photo of him running for sheriff in Aspen.

I also once worked as a Playboy Rabbit at a Playboy Club in New York, back when Hugh Hefner’s daughter had taken over the franchise. They were big swinger’s spots in those days. I was about a foot and a half shorter than everyone else, including the women, and had the full Chippendales-style look: collar, cuffs, no shirt.

TMR: Like the SNL sketch with Chris Farley.

MS: Exactly. I kept the collar and cuffs.

Probably the most heinous thing I ever took was a silver coaster from the U.S. embassy in Nepal. I’d just interviewed the king and president there. No idea why I took it, but I did. Mostly, I try to do what my mother said: “A good guest never leaves any sign of their presence.”

I’ve always felt I took a lot from people in order to do what I did. There was a writer named Bob Greene, he once said, “The business I’m in is a strange one. We scrape people’s insides for a living.” I used that as an epigraph for one of my collections.

TMR: Carrying on the family legacy in a different way.

MS: My father was an early Planned Parenthood doctor, an OB-GYN. I was trained as a scrub tech and worked with him, but I always felt I should do things differently. Tom Wolfe wore all white; I decided I’d wear black.

Most reporters come in blaring questions. I preferred to come in, stop, look, and listen. Sit by the fire, hang around, and only start asking questions once I understood what was really going on.

TMR: We often talk about personal style, how what you wear signals who you are. I’m curious if you thought about that when reporting, whether you dressed to blend in, or used clothes as a tool.

MS: The clothes were part of it. I wore black because you could travel, spill soup, and no one would notice. You could look decent anywhere. But more than that, by the time I was 24, most of my hair was gone. I have this funny series of press passes from my years at The Washington Post. At 21, I look fresh-faced, and by 1984, I look like a grizzled lunatic.

By 1986, I was turning 30 and decided to take time off. I was freelancing, approaching 30 with just a fringe of hair left. I went to this fancy salon, paid 30 bucks to trim it, and started growing a little tail. I stopped myself. When I got to Hawaii, I went straight to a barber and said, “Shave it off.” This was 1986, three years before Michael Jordan shaved his head.

The only people with shaved heads back then were Telly Savalas, Yul Brynner, and Isaac Hayes. Maybe not even Kareem yet. So becoming a bald guy was unique. I’m very dark-complected, so in summer I got really dark, black hair, dark skin. Wherever I went, nobody knew what I was. Cops thought I was a criminal, criminals thought I was a cop. No matter what country I was in, sirens went off and fences came down.

It was interesting, I’d be standing in line with a $10,000 check at the bank, and the woman in front of me would clutch her purse. I realized the first thing people thought when they saw me gave me an advantage.

So I learned: give people what they need. I always try to start with kindness and honesty, but you can tell what people need. People need to put you somewhere in their head, to categorize you. So as soon as I’d say, “I’m Mike Sager from Rolling Stone or Esquire,” it made sense to them. “Oh, okay, he’s not a scary guy, he’s just a weird writer.” Once they had that framework, I had them.

It’s a form of manipulation, but it helps you get along. You have to read people like a Tesla reading the road and respond in real time. I’m sort of an expert at intuition and body language. Maybe I was born with it, or I honed it, but it’s essential when you’re always the stranger in a strange land.

Having the bald head and earring, it was like a flashbang. A shock, then disarm. “Okay, now I’ll show you who I really am.”

Later, I was in Santa Monica meeting with Mark Burnett, the Survivor creator. I told his assistant, “I’ll be the guy with the shaved head, beard, and earring.” She said, “Which one?” That’s when I knew my time as the bald guy was over. But for a while, that was my brand.

TMR: That was your brand before branding.

MS: Exactly. It distinguished me, and it was useful. Not just as identity, but as a tool to get people comfortable, real, natural. My clothes were always nondescript, mostly black. When I moved to California, I had to add lighter colors for the daytime. You can’t wear black in the sun.

TMR: So does that mentality carry over to how you buy things now?

MS: I think so. For a long time, I only wore my own “uniform.” White shirts, white T-shirts, a long-sleeve dark shirt. I looked a bit like a priest, which I liked; it set a tone. But a few years ago, I started dating an Iranian woman who likes to dress up, so I’ve bought some clothes and shoes. Before that, I had one of everything, just enough to go anywhere.

Now I have a few more, but I focus more on where I live than on what I wear. That’s where I spend money now. Recently I replaced the fascia around my house because of termites. So yeah, no watches for me right now.

TMR: So it’s more macro-level spending than micro.

MS: Exactly. La Jolla is a strange place. It’s very consumerist. I often say people here have more dollars than sense. Everyone has the newest, most expensive car. People pay for everything in cash. I’ll go to lunch, and all these women are paying cash. Guys at dinner, cash. I know that’s undocumented cash. Then it’s, “We’re flying to Santa Monica for a Chanel party. My girlfriend’s got a plane.”

There’s a “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” energy here. It makes me even less consumerist. But I do believe when you spend money, you should spend it on good things, things that last.

I have furniture I bought when I was just starting out. My best friend-slash-drug dealer-slash-antiques merchant sold me Stickley furniture, Arts and Crafts movement stuff, Frank Lloyd Wright, Stickley Brothers, Tiffany. Every year, if I had money left over, I’d buy a piece. Stickley believed the mission of furniture was to last long and increase in value.

I still have a Stickley library table from 1910. My LG TV sits on it. It’s immaculate, beautiful. In the original catalog it sold for $10. Brad Pitt still collects this stuff. Barbra Streisand was buying $700,000 pieces from my friend. It’s increased in value, but also it’s heavy as hell, hard to steal.

So yeah, I don’t have a lot of furniture, but I have a few things that matter. Stuff won’t make you happy. You just need to be comfortable.

TMR: Right. The “buy less, buy better” idea.

MS: Exactly. Less is more. That’s also something that informs my writing and publishing. It’s a style, like the old rule from women’s magazines: before you leave the house, take off one thing. I think that’s a great rule.

My fiancée, though, would say the opposite, more is more. That’s her culture. Luckily, we have two separate houses. I’ve got my wood furniture; she’s got her bling. Somehow it works.

TMR: I’d love to hear more about The Sager Group, what inspired it and what the idea was behind it.

MS: Our slogan actually came from an interview I did long ago when Ice Cube left N.W.A. and was making his first solo album, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted. It was only the second hip-hop story Rolling Stone ever did.

I spent time with him while he was recording, and at one point he went on this amazing rant about wanting a Black lawyer, a Black accountant, owning your own label, all that. He said something about harnessing the means of production, kind of bastardizing Marx. That line stuck with me.

Years later, when e-books came out, it came back to me. I had five books with major publishers, and suddenly my work appeared online as e-books without anyone asking me. They apparently had the rights. So I called my publisher furious, asking why my best collection, Scary Monsters and Super Freaks, wasn’t available as an e-book. They said, “Oh, we don’t own the rights to that one.”

So I thought, “Great. I’ll learn how to make one myself.” I had a husband-and-wife IT team; she was brilliant and figured it out. Once I saw we could do that, I thought, “This is fun; let’s do more.”

This was around 2010 or 2011, when the magazine industry was starting to crash. I was debating with my mentor; he said everything was dying, and I said, “No, it’s evolving.” I told him, “I figured out how to publish books; let’s do one together.”

We put together a collection called Next Wave featuring young writers, Seth Wickersham, Wright Thompson, all these people who later became huge. We nailed them all in 2011.

Then my IT person went to Europe for three weeks right before our deadline, and I had no idea how to publish a book. Luckily, one of my former students, this aimless kid who later became a tech guy, visited and said, “I can help you with that.”

So with his help, we built the company. At first, people in Romania, Transylvania no less, handled the uploads and listings on Amazon. I was self-taught. No gatekeepers. I could finally be King Sager.

My whole career, I’d been supplicating, editors on one side, sources on the other. Without either, I had nothing. Now I had my own sandbox.

I also had this philosophy I call the “Theory of Originals”: be number one in a class of one. Don’t compete, define your own lane. That came from being a 5’3” walk-on soccer player at Emory. I couldn’t be like everyone else, so I had to be different. Same at The Washington Post, everyone was Ivy League. I couldn’t be them, but I could be me.

With The Sager Group, it’s the same. Our business model isn’t selling books, it’s making them. Writers pay me to make them, and they own most of the rights. Even major authors now need their own marketing plans.

I remember one publisher gave me $9,000 for a book, and I did a 39-stop tour that I planned myself. What’s the difference? Now, I make the rules. Some of my authors are Pulitzer winners; others are writing their first books. The amateurs pay for the pros, but they’re all on the same shelf.

It helps that I don’t pay myself, my company couldn’t afford it. I used to make $7 a word; now it’s five cents.

So this is my job in semi-retirement. I’ve thrown away my fucks and just do what I want.

I’ve realized over time that I have what I call a ministerial heart. My father was an OBGYN, but he had that same kind of compassion. It’s something I inherited. You have to know what people need before you can get what you want from them.

When I was in sixth grade, I was the kid everyone came to with their problems. Later in life, other writers did the same thing. David Granger, the Esquire editor, came to me for advice before writing his first story. We weren’t even close friends then. I’ve always been the advice giver.

At some point, one of my mentees said I should call my company “The Ministry for Wayward Writers”. In a way, that’s what The Sager Group is. It’s a place where I get to do everything I’ve enjoyed and become good at over the years, and make my life exactly what I want it to be.

To me, that’s the real definition of success, shaping your life on your own terms. No alarm clock.

TMR: That’s the goal.

MS: Though I still get up at the same time every day. I have a routine. I commute 47 steps to my office.

When I think back to when I worked at The Washington Post, I lived downtown in D.C. but had to drive an hour out to the Fairfax Bureau. No highway, just stoplights the whole way. I remember thinking, “This makes no sense.”

The idea of carving out your own life, of defining your own class of one, is what matters. Not necessarily being the best in the crowd but being the only one doing what you do.

TMR: It seems like a natural progression for you, given how independently you’ve always worked.

MS: Yeah, totally. I was never smart or ambitious enough to have a grand plan. I never thought, “I want to be a writer.” I just followed what interested me.

Before I got to The Post, I’d never really read newspapers. I didn’t like literature in high school. I led English discussions based on nothing. My mother used to say I was a good bullshitter.

I’ve since gone back and read all the books I skipped. During COVID, I read a lot of the American canon. You appreciate it more as an adult.

But yeah, if you can carve out your own life, that’s everything. I never wanted to have to “call in sick.” As a freelancer, you just deliver: on time, five words under the limit, a day early. It’s not enough to be good, you have to be reliable.

TMR: That’s true.

MS: You give people what they want, and they’ll keep coming back.

TMR: Is there a specific piece of writing you’d recommend, something you’ve read recently or revisited?

MS: Hmm. When people ask me that, my mind always goes blank. But I’ll say this: for fun and easy reading, go back to Larry McMurtry’s early series, the ones that include The Last Picture Show. It’s part of a four- or five-book cycle. You could start there. It’s a perfect little book.

TMR: It’s interesting how Lonesome Dove has had a huge resurgence lately. Esquire even did a story on that.

MS: No kidding. My girlfriend and I at the time both loved when they “went and got a poke.” Great terminology.

This was a great read. Love how you talk about building outside the usual gatekeepers and carving your own path. That’s exactly what my wife and I have been doing, piece by piece, building something from the ground up. We’re approaching nearly 100k subscribers on YouTube with a lot of hard work and dedication over the past 6 years. Onwards and upwards!